By: Adam D’Addario

Ophelia Black is a 22-year-old woman from Calgary who has taken a prescription for Dilaudid, an oral hydromorphone that she has taken three times a day for the past two years. Black was diagnosed with severe opioid use disorder and says her prescription has prevented a potentially fatal fentanyl overdose. “In the two years that I have had my prescription, I haven’t overdosed on it at all because as long as I have my medication, I don’t take anything else. I don’t want to take anything else.”

One of the changes to NTS requires “witnessed dosing of high potency opioid narcotics at the location of the licensed clinic.”

This means that patients like Black must be monitored while they take their prescriptions at a clinic located in downtown Calgary. The government has not specified why they require this, but Black says it is unreasonable for someone like herself who has to commute two hours each way to get downtown.

On top of that, by March 4th, Black and patients like her will be stripped of their prescriptions entirely while being told to transition onto opioid agonist treatments like suboxone and methadone with few exemptions.

Black is fighting to keep her prescription. She says, “if this keeps me safe and keeps me alive, then it’s really important that I’m allowed to stay on it.” That is why she is suing the government.

“The Alberta Model”

This is not the first time the Alberta government targeted a harm reduction service. One of the very first things the United Conservative Party (UCP) did when they came to power in 2019 was immediately put supervised consumption sites (SCS) under review.

The review’s findings focused less on the efficacy of these sites and more so the economic impact on nearby properties and businesses. The results were called out in an open letter by scientists and scholars who say the UCP used “unsound research methods and deficient analytic procedures.”

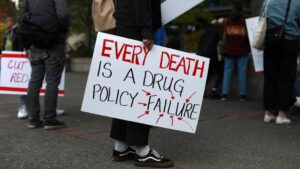

Alberta’s recovery-oriented approach has been dubbed by the government as The Alberta Model, and has resulted in at least three lawsuits so far from people who use drugs, harm reduction workers, and drug policy advocates.

BC’s newest program

Last month the British Columbia government began a three-year pilot program decriminalizing the possession of 2.5 grams of opioids, crack/cocaine, methamphetamine, and MDMA. Ophelia Black moved from BC to Alberta when she was younger and says, “if I still lived in BC, I know I would be more taken care of.”

BC has run a limited safe supply program in Vancouver for over a decade and, in 2022, began a program prescribing fentanyl.

This is being done as an effort to provide a safer alternative to the fentanyl that’s on the streets, prevent fatal overdoses, and bring stability to the lives of drug users in Vancouver.

Now BC is taking it one step further. From January 31st, 2023, lasting until 2026, the BC government began its decriminalization pilot program.

Depending on your personal beliefs about drug use, BC’s decriminalization program either sounds like great news or a horrible idea. But for some drug policy experts, it only sounds like an ok idea.

Nicole Luongo works for Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. An organization focused on developing a drug policy in Canada based on science and guided by public health. Luongo says that BC’s current safe supply programs are too limited and that they are framing this decriminalization program as a means to lower overdose fatalities. “Decriminalization alone does not introduce safe drugs into the supply.”

A federal solution?

Although provinces and municipalities can seek exemptions, drugs remain a crime enforced by a federal law known as the “Controlled Drugs and Substances Act” (CDSA). While the Canadian government has supported some safe supply programs around the country, they have been unclear on a federal plan to source a safe supply.

This comes after an expert task force recommended the government create a safe supply of substances to reduce people’s reliance on toxic street drugs well over a year ago.

Alberta and BC may be close in proximity but are miles apart on drug policy. This trend persists across Canada in how other provinces design their drug policies.

Luongo is not the only expert calling for a national strategy for the overdose crisis that involves decriminalizing and regulating drugs.

When it comes to everyday Canadians, polling from the National Library of Medicine shows that 55 percent are in favour of supervised consumption sites, and only 49 percent are in favour of low-threshold opioid agonist treatments like methadone. A poll from Research Co. and Glacier Media shows that only 40 percent of Canadians are in favour of the decriminalization of all drugs.

So while advocates and experts agree that the lack of a national strategy is the reason for drug policy disparities from province to province, the politics are guided by public support rather than public health.

Be the first to comment