By: Joey Seppelt and Raissa Santos

Nathanael Azevedo, a voice actor in the Greater Toronto Area, says he is careful scrolling through open casting websites these days. He fears the possibility that his voice could be stolen.

“It’s the wild west.” – Nathanael Azevedo

Azevedo says dubious postings on these sites will claim to be authentic. But their real intention is to feed your vocal data to a complex algorithm that aims to replicate it.

“You gotta (sic) really pay attention to what these casting calls want from you and what they’re asking from you. Because there is a lot of shady stuff out there.”

He says some sites are cracking down on the issue. But with no copyright protection over his voice, Azevedo and other performers around the world fear they might end up losing value in the entertainment marketplace.

The history

The crossover between voice and machine is not a new development. Synthetic speech has been around for several decades. In 1961, IBM introduced a machine that could recognize sixteen words and nine digits. More than twenty years later, Dennis H. Klatt combined his voice with speech algorithms to create the synthetic voice system used by Stephen Hawking.

The dawn of the 21st century has seen technology further envelop itself into our lives. 2011 saw the emergence of Siri. Other corporations started to take note. Then Alexa and Google Assistant entered the picture. Tasks such as setting timers and answering questions could be activated on demand.

Then came the recent artificial intelligence boom. Statista is forecasting a worldwide annual growth rate of 15.83% for the industry from 2024 – 2030. By 2030, the market value is expected to be $738.80bn.

Google Trends data measuring search terms. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. Values reflect how many searches have been done for the particular term relative to the total number of searches done on Google.

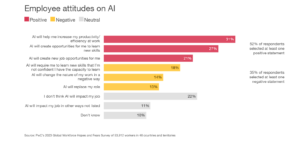

With such massive technological developments, the threat of automation is real.

The voiceover industry is being affected by these changes. The process of recording an audiobook with human narration can now be replaced by automated speech algorithms. Same goes for dubbing content in other languages. Why hire a human actor when it is much more profitable to generate different languages through a computer?

What’s being done about this?

Alistair Hepburn, Executive Director of performers’ union ACTRA Toronto, says NIL (name, image, likeness) rights need to be expanded to include voice. He says ACTRA is pushing for the government to include this in the proposed Artificial Intelligence & Data Act.

Hepburn says these worker protections need to be a worldwide effort. He cites the United States’ “No AI FRAUD Act” and the European Union’s similar propositions.

Because of these developments, he remains cautiously optimistic. He says the government has been willing to engage in talks. But Hepburn also acknowledges that these processes are never quick and easy.

“Just like we protect the corporations and their brands, we need to protect the individuals and their brands. Their name, their image, their likeness, and their voice.”

Nathanael Azevedo hopes AI can be a tool rather than a hindrance. But he acknowledges that corporations still stand in the way of regulations.

“I hope that there’s a good balance that is eventually found. But I’m not sure we’ll see that for a long time.”

Be the first to comment