By: Jason Saunders

You might have seen the term “Anthropocene” popping up recently. It’s been used in scientific, environmental, and literary communities for over 20 years. To outsiders, it might be unclear what the word means – or why it’s been sparking debate for the last two decades. It’s very conception asks the question: are human beings the greatest vector for change on this planet, and are those changes irreversible?

Officially, the Earth is in the “Holocene” epoch. The term means “entirely recent”, although that may be a bit misleading. The Holocene started approximately 11,700 years ago, at the end of the last major ice age.

Some experts argue that the Holocene is over. They say that because of humankind’s impact on the planet – global climate change being chief among them – we have entered a new epoch. This is what they call the “Anthropocene” (anthropo meaning “man” and cene meaning “new”).

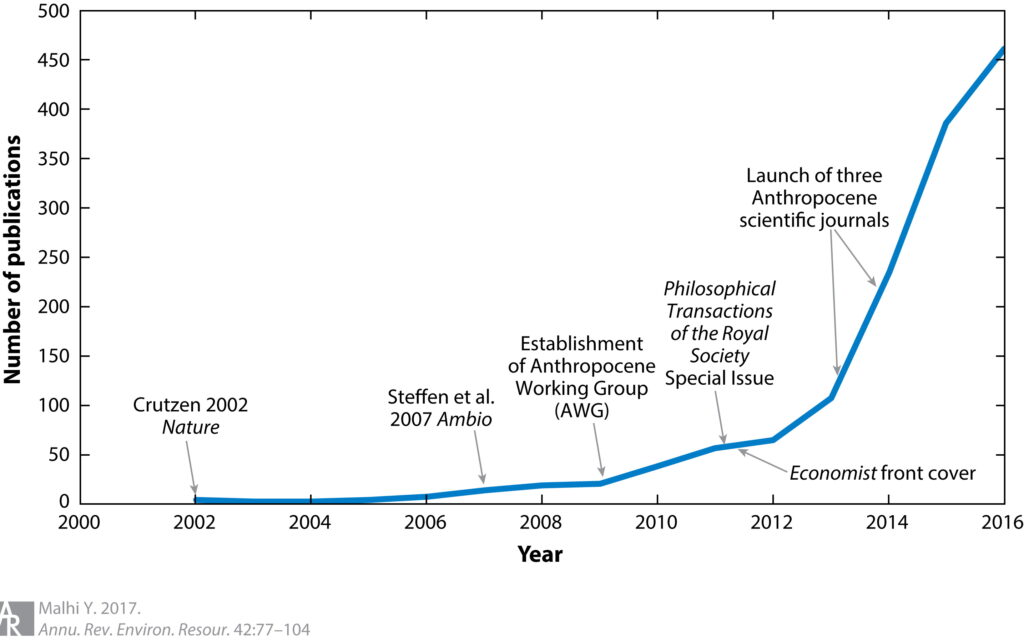

The term was popularized by Nobel prizewinner Paul Crutzen in 2000. Since then, it has become a mainstay in a number of circles. Below is a graph made by Yadvinder Malhi from the University of Oxford detailing it’s frequency in peer-reviewed scientific publications up to 2016. Professor Crutzen passed away last year, but his legacy lives on in our language.

last year, but his legacy lives on in our language.

The term isn’t without its issues. A primary critique of the word is that it lumps all human activity and behaviour into one group, as if we are all equally responsible for the mass change that humans as a species have had on the planet.

Additionally, there is no clear consensus on when the Holocene ended and the Anthropocene began. Some scholars put the date as early as the advent of agriculture, about 10,000 years ago. Others put the date around 1800, citing the start of the industrial revolution. The most popular start date among scholars is approximately 1950, when nuclear tests began to forever alter the Earth’s atmosphere. Without a governing body like the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) to determine if the Anthropocene is indeed real, let alone when it started, these issues are unlikely to be resolved anytime soon.

Even still, the term has had no issue evolving from it’s geological roots and spreading to the humanities. Many scholars in the fields of history, philosophy, and cultural studies have adopted the word as a way to explain the age we live in, and in turn, our response to it.

The 20th century marked the beginnings of the post-apocalypse genre as we know it today. That’s not to say the genre didn’t exist before 1900 – there are some very notable examples of story worlds that take place after some kind of widespread disaster from the preceding century. Lord Byron’s Darkness from 1816 is perhaps the earliest example, and H.G. Wells’ 1897 War of the Worlds may be the most famous.

From the mid 1900s on, humanity began to go through globe changing events. Some had never been seen before, and others were familiar to us as a species. Two world wars and the invention of nuclear technology, followed by global climate change and more frequent environmental disasters, advancements in space travel, fossil fuel scarcity worries and renewable energy, the advancement of modern technology and the birth of the “technological singularity”, and perhaps most topically, pandemics. These are all rich topics to draw inspiration from for stories about the end of the world, and it’s not a coincidence that these all take place at the most commonly agreed upon start of the Anthropocene.

Whether or not we realize it, and whether or not you agree that we are in the Anthropocene, it’s an idea that has permeated our culture deeply and permanently. Humankind’s impact on this planet is inescapable, even in our fiction. The threat of nuclear war has inspired the likes of the Fallout video games and the cartoon network show Adventure Time. Energy scarcity brought us stories like 2015’s Mad Max: Fury Road. Space travel and alien theories inspired stories like Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide series of novels. Fears of modern technology gave us stories like The Matrix. The list goes on and on.

Perhaps the greatest example of a story inspired by the Anthropocene is one that predates the term by decades. Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel Dune has the study of ecology, the impact humans can have on a planet’s climate and vice versa, at its core. The story remains relevant to this day, with last year’s film adaptation receiving a nomination for Best Picture at the Oscars.

The reason that these stories can stand the test of time, remaining in the cultural zeitgeist for decades after their release, is because of the Anthropocene. Or, at least, something like what the Anthropocene is supposed to represent - that human beings have a massive, undeniable, irreversible impact on our world. Our appetite for post-apocalyptic stories is simply a byproduct of that immense impact. After all, we will write what we know.

Be the first to comment