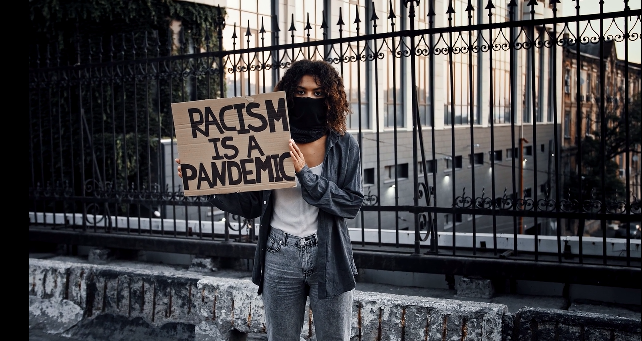

Racism is a pandemic. Black, indigenous people of colour (BIPOC) have dealt with the double sword of the colour-coded agenda. It is an agenda that highlights the discrepancies of the impacts of racism found in working environments, the justice system and in this case, the healthcare industry.

There’s a blind spot in the healthcare industry, and BIPOC continue to endure improper medical attention due to specific social determinants such as income, housing, education, systemic racism and or access to proper healthcare.

The cause of this reality also highlights poverty, oppression, cultural differences, gender, discrimination and lack of research.

A CBC news interview with Dr. Modupe Tunde-Byass, a Toronto obstetrician-gynecologist and president of Black Physicians of Canada, quoted her stating that "For our country, we don't have (the) data. So it's difficult to know exactly what we're dealing with. We can only extrapolate from other countries."

The numbers are more troubling when the data is not collected.

In the U.S, studies show that maternal mortality is higher for Black women, irrespective of income or education level.

Black women are 3–4 times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than their white counterparts.

Infertility affects at least 12 percent of women of childbearing age. Studies also indicate that although 20 percent of Black women experience infertility, only 8 percent seek medical assistance.

According to the previously mentioned CBC news article, Black babies are more likely to be premature. However, Dr. Tunde-Byass stated that the only race-based study that examines the discrepancies of pregnancy was conducted at McGill University in 2016. The study was regarding the disparities in preterm birth.

Pain is an indication of labour.

If medical health practitioners dismiss pain concerns from their patients, they'll become more prone to vulnerable infections and diseases, weakening the metabolic and immune systems over time. Women of colour (WOC) would often be given less to no pain medication due to the pain eventually 'going' away.

Toronto resident Kimitra Ashman said she felt she was ready to give birth earlier than 40 weeks of gestation, a timeframe more common in white women. But she said she was dismissed, even though Black women often have shorter gestation periods.

A Toronto resident, Andrea Sierra, a new mother, just learned that racism isn’t just something that happens to someone else. During her pregnancy and birthing experience at Sunnybrook Hospital, not only did she encounter racism in the healthcare industry, but the experience impacted her overall medical care and wellbeing.

"Towards the end of the third trimester, they need to start checking your cervix and to see if you're dilated. I was 36 weeks pregnant, and I had an appointment with my doctor on a Tuesday. I asked her if it was time to start checking my cervix, which she should have started checking the week before. And she goes, "no, we'll start next week." And the next day, I went into labour. And had she checked me, we would have seen that I was already dilating," said Sierra.

Andrea speaks out about the racial inequities that she and other women of colour experience in healthcare daily and how the cuts run more profound in the midst of a pandemic.

The miscommunication and microaggressions are partially the reason why race-based data research is prudent. Without it, the medical industry cannot overturn its biases, extracting them from unconscious bias.

The Covid-19 pandemic

The physical and mental health plights that BIPOC experience create a visceral response on how they'll view healthcare and doctors' intentions. There's an ongoing generational mistrust towards healthcare services, which explains why there is a fear of seeking medical health. Now with COVID-19 affecting more BIPOC, the conversation needs to drive action.

Raywat Deonandan, an epidemiologist at the University of Ottawa, told CTV that "In our society, race is correlated with wealth, and wealth is correlated with behaviour, and behaviour is correlated with exposure. BIPOC are at a higher risk of being infected with COVID-19 due to social and economic barriers."

Be the first to comment